Prometheus and the Fire of the Soul: Indo-Aryan Echoes

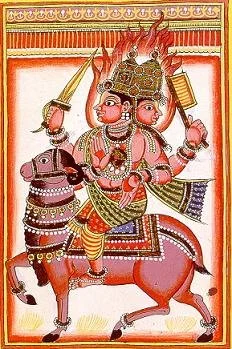

Agni, the Vedic god of fire, shown on a ram

Why does Prometheus still haunt the imagination of the West?

In an age of technological acceleration, cultural fragmentation, and existential yearning, the myth of Prometheus seems more alive than ever. He is the rebel who steals fire from the gods and brings it to mankind—the Titan punished for his defiance, chained to a rock, liver eternally devoured by an eagle. To many, he is the first revolutionary, the archetype of the modern spirit: heroic, tragic, indomitable.

But the myth of Prometheus is older and deeper than modern ideology. It speaks to the fire within the soul—the inner light of striving, sacrifice, and illumination. This article is an invitation to rediscover Prometheus, not as a one-dimensional symbol of rebellion, but as part of a sacred tapestry of spiritual longing that spans Indo-European, Zoroastrian, Vedic, and Christian traditions.

I. The Stealing of Fire

In Hesiod’s Theogony and Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound, the Titan Prometheus defies Zeus by giving fire to humanity. In doing so, he sparks civilization itself—offering light, heat, craft, and divine resemblance. But Zeus punishes him savagely: he is bound to a mountain in the Caucasus, where an eagle tears at his liver each day, only for it to regenerate each night.

Prometheus’s crime was not merely theft—it was hubris. He blurred the line between mortals and gods. He transgressed sacred boundaries. And yet, in his suffering, there is a nobility, a willingness to endure pain for the sake of a greater vision.

He is not just the rebel; he is the bearer of divine fire.

II. Echoes Across the World: The Indo-European Fire-Bringers

The archetype of the fire-bringer is not confined to Greece. It appears—though in different forms—across the Indo-European world and beyond. In these traditions, fire is never merely a physical force. It is sacred. It is initiatory. And those who bear it walk a dangerous path between worlds.

Agni: The Divine Mediator

In the Vedic tradition of ancient India, Agni is not simply the god of fire—he is fire itself: the flame of sacrifice, the divine messenger, the mouth of the gods. He mediates between earth and heaven, carrying offerings from mortals to the divine realm.

One of the earliest hymns of the Rigveda invokes Agni as “the priest of the sacrifice,” the one who knows the paths of the gods. But the myth of fire's arrival on earth is tied to Mātariśvan, a mysterious figure who retrieves the hidden flame and delivers it to the Bhrigus, an ancient clan of sages descended from Bhrigu, one of the seven great rishis.

This act is not punished but revered. Unlike Prometheus, Mātariśvan is celebrated by the gods for bridging the gap between the human and divine. Yet the spiritual resonance is the same: fire must be carried, protected, kindled. It is a force of transformation, not possession.

Even today, Hindu ritual preserves this sacred continuity. The saptapadi—the seven steps taken by a bride and groom around a sacred hearth—invokes fire as the divine witness to their vows. In Agnihotra, fire is kept burning in the home, sanctifying domestic life and reminding the household of the eternal cycle of purification, offering, and rebirth.

Agni, god of fire, shown riding a goat (18th century miniature)

Zoroastrianism: Atar and the Light of Truth

In the Zoroastrian tradition of ancient Iran, fire (Atar) is venerated not as a deity, but as a visible symbol of the divine order (Asha), the principle of truth, justice, and cosmic rightness. In Zoroastrian fire temples (Atashkadeh), the sacred flame is kept perpetually burning and meticulously tended by priests. It is not a symbol of rebellion—but of eternal vigilance.

The flame is believed to purify, to expose falsehood, and to mediate between the material and spiritual worlds. It serves as a divine witness to oaths, as well as a force of interior illumination. One does not steal this fire. One guards it. Tending the flame is a form of spiritual custodianship—a Promethean act transformed into sacred responsibility.

Even the act of consecrating a fire involves collecting flames from multiple sources—forge, hearth, lightning—and ritually purifying them before enthroning them. In this theology, fire is divine not because it is powerful, but because it is pure. It burns without corruption.

Scythian Mythology: Tabiti and the Flame of Sovereignty

Often remembered as fierce horsemen and steppe nomads, the Scythians in fact cultivated a noble warrior culture rooted in fire, oath, and ancestral honor. Originating in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, the Scythians were a confederation of Indo-European tribes whose society, according to historian Ricardo Duchesne, was defined by aristocratic egalitarianism—a world where leaders were not bureaucrats, but the first among warrior-peers.

At the spiritual heart of Scythian life was Tabiti, the burning goddess—their version of Hestia, or perhaps Atar. Described by Herodotus as queen of the gods, Tabiti embodied the sacred hearth, the divine center of tribal order. Her fire was not housed in temples, but in the mobile hearths of chieftains—living symbols of divine legitimacy.

Breaking an oath sworn over Tabiti's flame was punishable by fire. In this culture, fire is the guarantor of truth, honor, and sacred kingship. It may echo the Iranian concept of Khvarenah—a word meaning “glory,” “splendor,” and divine favor. But unlike the fire of the Zoroastrian priesthood, Tabiti’s flame was carried by nobles—it traveled with the people, embodied in the chieftain’s presence and the camp’s sacred center.

This vision of fire is neither theft nor temple cult. It is transmission through lineage and merit—a flame passed on by the worthy. A sacred Prometheanism not of rebellion, but of earned sovereignty.

III. Toward a Sacred Prometheism

The fire myths of the Indo-European world do not contradict Prometheus—they complete him.

In Vedic India, fire is given but must be kindled. In Zoroastrian Iran, fire is sacred and must be guarded. In Scythian society, fire is authority itself—enthroned in the heart of the noble. Prometheus, in this wider context, is not merely the rebel. He is the prototype of the priest-king, the one who bears divine light at great cost.

He suffers not because he broke the rules—but because the world was not ready for the flame.

Perhaps now, in an age of cold machines, broken myths, and flickering meaning, we must return to these older fires. Not to repeat them—but to rekindle their light.